Trains of Tokyo

This post is about how we got around Japan.

Our journey began on a direct flight from Los Angeles that curved along the Pacific Rim and, to my surprise, even over Alaska and its Aleutian Islands until Cape Inubō materialized from the mist.

Our path through security started out smoothly thanks to pre-registration of our documents. We’d cruised past the first checkpoint when a woman stepped in front of us and roped us off.

The problem wasn’t so much that we waited half an hour — watching another line breeze past as officials invited select passengers from behind us to circumvent us — or that the hallway got increasingly hot as it filled with people. The problem was that we couldn’t understand Japanese and thus had no idea why we’d been stopped or when it would end. We waited, powerless to do anything but, and eventually, like cattle, they herded us onward.

An hour or two later, we emerged free from customs. It was time to figure out how to get from this airport out in Chiba Prefecture to our hotel in Minato City, one of the Special Wards of Tokyo. The cabs looked expensive and would barely save any time versus the train, so we lined up to buy tickets for the Skyliner. Only upon reaching the front of the line did my tired brain realized the kiosk was in Japanese. I stubbornly stumbled my way through, making my best guess as to what each option meant, before Corey asked the man behind us for help. He navigated us to checkout before showing that, all along, we could have toggled the screen to English. If that wasn’t embarrassing enough, I then realized the machine didn’t take credit cards, so I ran to the currency exchange while Corey lined up at the full-service ticket counter and we ended up buying paper tickets using paper cash from a real person.

Tickets in hand, we rushed off, in danger of missing our train. I sought the platform that matched the color of the one listed on our Google Maps nav, but the train number was wrong, so we ran back and asked for directions before rushing downstairs to the platform, flustered and sweating. We stepped on the train one minute before departure time, and it started moving before we’d sat down. Realizing we were in the wrong car, we lurched through cabin after cabin before finally collapsing into our seats.

Notwithstanding a small snafu at the transfer point — involving a mix-up between ticket & receipt, Google Translate, and a few unnecessary trips up and down the stairs — we made it onto the Tokyo subway system. We set off aboveground in a sparkling-clean car all to ourselves. The train went underground as we approached city center and eventually filled up.

At our final destination, Shimbashi Station, we tried leaving but the gates at the exit blocked our way, a red alarm blaring when we tried to bypass it. Other people scanned their phones or plastic cards, but our paper tickets’ usefulness had come to an end. At a loss as for what to do, we noticed a dude with a laptop sitting on the floor. After we’d communicated our problem, he shook his head and ran with our tickets to the counter and back before relating — in so many words and gestures — that our tickets were spent but that he’d let us go.

We emerged into a wet night and dragged our bags in the direction of the hotel, through crowds and over crosswalks. The way there looked far simpler on my map than in practice. Side streets looked like dead ends, and dead ends forced us to search for underground tunnels or overpasses. Our first experience navigating Tokyo felt like navigating a maze.

Eventually, we found stairs to the overpass that should deliver us to our hotel’s entrance. Corey was especially exhausted, so I took all three suitcases while she walked on ahead. That’s when a man approached and asked if we needed help. I felt like I had in Patagonia when I’d been struggling down the mountain and offered hiking poles; I had no choice but to set aside my pride and accept.

As we lugged the bags together, he struck up a conversation. “Where are you from?” “Los Angeles” “Ahh I lived for 5 years in LA! Hollywood and San Gabriel Valley. Before that lived in NYC for 16 years” “So did we! Before we met. I lived on the east side of Manhattan.”

He shepherded us to the escalator that would take us down to the hotel. Such an entrance, accessible only from an overpass, reminded me of the Nautilus’s secret base in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, an island cove accessible only from underwater. Like a submarine ascending from the deep, we descended from on high to the secret entrance to the Conrad Tokyo.

We spent two quiet nights there with long peaceful mornings as we adjusted to Asia. Such luxurious accommodations had come courtesy of a speaking engagement Corey had done with Hilton corporate, and we felt like overseas royalty.

Our second hotel, the Shinagawa Prince, was quite a different story.

Not that there was anything so wrong with the Prince, besides that our room was so small that we could barely open our suitcases. The main issue was that, given this marked the commencement of the official ‘UCLA Trek’ leg of our journey, the Prince simply didn’t have the infrastructure to allow for easy flow of over 200 people trying to do the exact same things at the exact same time. For instance, when we arrived to drop our bags off so we could go explore the city before check-in, many classmates had the same idea, which created an hourlong line in the lobby.

The Shinagawa Prince got crammed at times but our room had sweet views

To get around the city, we mostly used the Yamanote line, an aboveground train that makes a full loop around the heart of downtown Tokyo. That day, after we’d dropped our bags and were waiting for the next train to arrive, we had our choice of hot and cold beverages from the platform vending machine and opted for a hot green tea that we passed back and forth to sip along our way from Shinagawa to Harajuku.

Riding the Yamanote line reminded me of books I’d read depicting the old-school Japanese streetcar. The biggest difference — besides that they don’t go on streets — has to be that today the Japan Rail train system announces upcoming stops not only in Japanese but in English too. Each ride on those trains felt clean, leisurely, and peaceful. We were safe from the rain outside yet free to gaze out at the pink trees blooming next to the tracks.

We generally avoided taking cabs. Not that there was anything wrong with them — the blue-green ones in particular looked pretty cool — but they were far more expensive as compared to the subway. A typical subway ride cost $1.50, whereas comparable taxi rides cost 20 times that. A downside of the subway, though, is that some stations were so big that we got lost. That’s what happened to us in Shinjuku Station, which we later learned is the busiest station in the world, processing an average of 3.5 million passengers per day.

We took one daytime excursion outside Tokyo to explore the area around Mount Fuji. For this, we took a bus, ostensibly the most efficient way to herd a large group of foreigners. On the ride out, our guide Yoko threw out some fun facts and I read a bit of my book, but mostly I stared out the window at the splendor of the downtown skyscrapers fading into residential neighborhoods, which stretched thinner and thinner until they intermixed with an idyllic landscape of wooded hills.

The mountains surrounded us before we’d even officially left Tokyo, so big it is. At about the time we crossed into Yamanashi Prefecture, Yoko commenced expectation management, warning that some days Mount Fuji is “shy” and doesn’t want to come out, choosing instead to hide behind the clouds. Today, the forecast indicated that it could go either way.

Then, soon after emerging from a tunnel, Yoko squealed and clapped, announcing that we were in luck. Indeed we could see… some of it. Far from the epic view I’d imagined, yet satisfying nonetheless.

We stopped for a bit at the Fujisan World Heritage Center before continuing into Kanagawa Prefecture. Yoko kept us entertained by leading an origami class. MBAs don’t necessarily make the best visual artists, but most of us succeeded at least in completing *drumroll* an origami Mount Fuji. Gui, on the other hand, went one step further, tapping into his 8-year-old self to make a kusudama.

The next tunnel we drove through deposited us into the interior of a cloud, and our next mode of transportation, in Hakone, took us even higher up, as we boarded the Komagatake Ropeway tram which took us another 2000 feet up into the sky.

After getting a closer look at the terminal, most were surprised to learn the tram was still in operation. It looked looked like the lovechild of Fallout 4 and Spirited Away, abandoned and neglected. It worked well enough for us though.

Back at the bottom, we waited for a boat to take us across Lake Ashi, fully expecting one of the two pirate-looking ships that had been featured on the tour’s website. But they both passed us by and we got stuck instead with a normal old ferry.

Ok, not as old as the tram. And we had a deck to sightsee from. The wind made it pretty cold up there, but the tranquility radiating out from the Heiwa no Torii or “Gate of Peace” calmed me. It marked where water met land, and I imagined it would be just the place for a trainer to walk through and climb onto the back of a Lapras.

The bus ride back to Tokyo was supposed to take 2 hours, but right away, on the single-lane road down from the mountains, we hit major traffic. Things got worse when we pulled over to a rest stop because someone who’d drank too much threw up in one of the other buses.

Back on the road, the traffic got worse and worse, and with the highway at a standstill we got a rather unwanted tour of an industrial town’s side streets. Yoko tried relieving the boredom by passing out maps of the Tokyo metro. A classmate, more successfully, entertained the bus by leading a round of karaoke. For most of the ride, I felt so overwhelmingly bored and frustrated that I couldn’t even bring myself to attempt active boredom relief, say, by reading my book. When the 4 hour ride came to a close, we almost stumbled over each other in our impatience to exit the bus. Stepping off brought intense relief.

We spent a little too much time on these

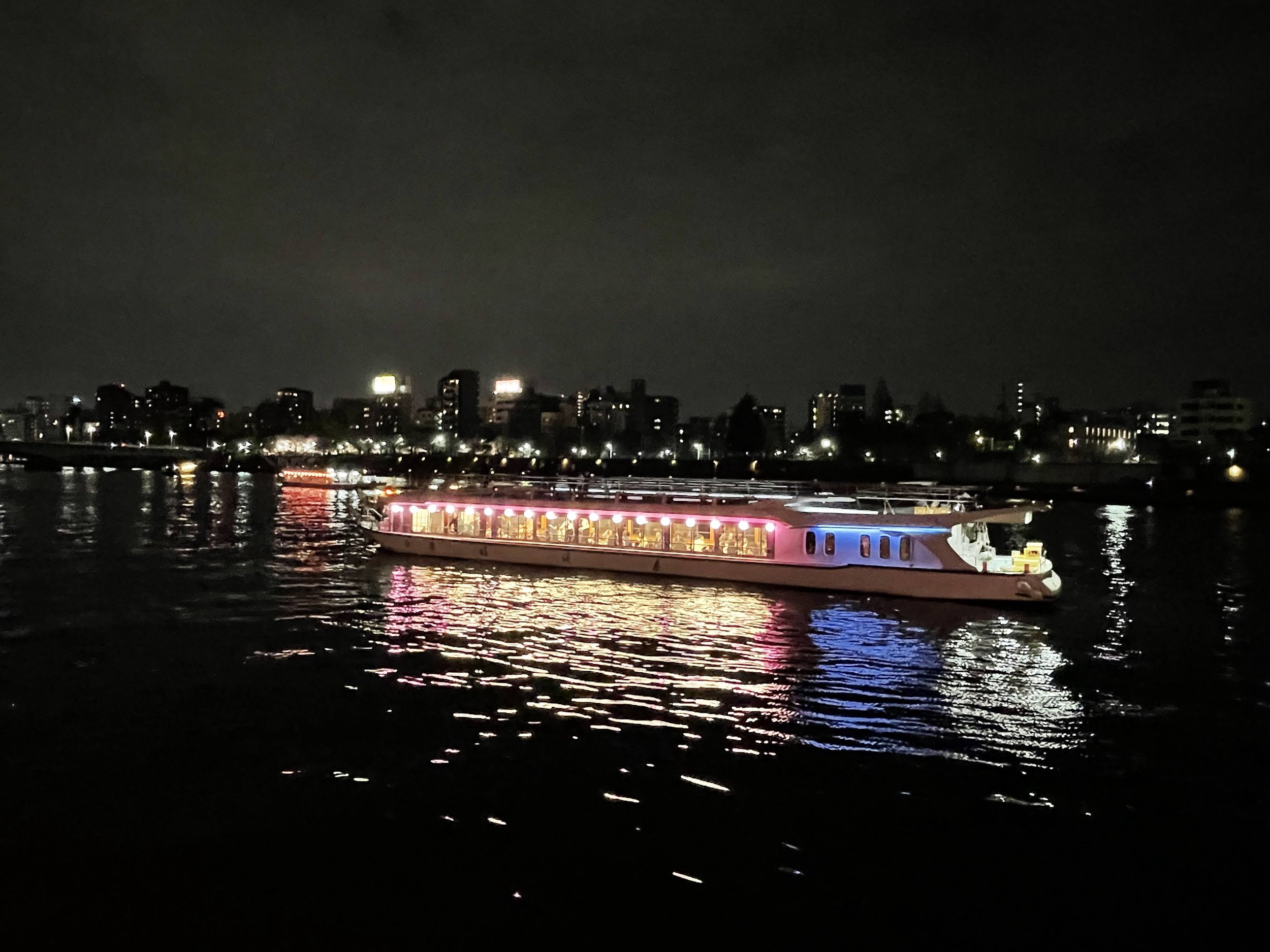

The next day we walked to Chuo City to meet classmates for dinner aboard a yakatabune boat that took us up and down the Sumida River. I’ll cover the party dynamic in a later post, but in terms of the transportation I most remember sitting on the floor yet barely noticing the river’s undulations; seeing other boats and their lanterns illuminating parties of their own; and passing under a wide variety of bridges.

The morning we checked out of the Prince, our trek leaders had arranged trucks to shuttle our bags to Kyoto while we took the train. That bag drop ended at 7:30am, so I thought I was well on time walking out of my hotel room at 7:15.

A couple classmates were already waiting for an elevator. One soon arrived, but it was completely packed with more Bruins. “Sorry!” Same deal for the next one, and the next. We were at least 20 floors up, too high to take the stairs with all our bags.

We tried pressing the up button, hoping that would yield an empty elevator, but nope, other floors had already thought of that. Occasionally, an elevator would have just enough room for one person to jam themselves in. But by now, each elevator took quite some time to arrive, thanks to each floor requesting stops in both directions. It was the prisoner’s dilemma of elevators.

It took twenty minutes or so before I made it into one, leaving a line of people behind. As we began our slow descent, smiling guiltily at every floor we stopped at, Ayesha said to me “you’ll have to include this in your travel blog.” I really felt bad for the people who weren’t in our program and just wanted to get down to breakfast.

They held the bag truck an extra twenty minutes in reaction to the frustration pouring into the trek’s Slack channel, so I got ours on in time. After breakfast, the entire group of over 200 people met up and walked to the station together. Our hotel had in fact been chosen due to its proximity to the Shinkansen, otherwise known as the bullet train.

The bullet train stops for exactly 1 minute at each station, as portrayed in the eponymous movie. So when it slowed to a halt at Shinagawa, we all scrambled on, Corey and I able to find two seats on the RHS of the train. Then it took off. In a blur — ten minutes, fifteen minutes, thirty minutes, I donno! — we’d already passed Hakone, covering the same distance that had taken us 4 hours by bus in just a fraction of the time.

I guess that’s the point of a 200 mph train. The foreground flashed by like a flipbook. We wove along the coast before heading inland, and even people running on just a few hours’ sleep woke up when we passed Mt. Fuji, who shyly peeked its head out to say hi.

In Kyoto, we met with quite a change of pace by staying at a traditional ryokan hotel, the Ishicho. On one hand, we’d gone from luxurious five-star accommodations to sleeping on a floor. On the other hand, those tatami mats are actually pretty comfy; the room was far more spacious than the Tokyo ones; and we got a feel for what it might been like for my paternal grandfather during one of his 25-30 business trips to Japan back in the 60’s. Oh, and we went out late every night and thus didn’t spend much time there outside of a few afternoon naps. The one thing I regret missing out on is the public bath in our hotel’s basement, which I’d read about in books such as And Then. We simply didn’t have the time.

The final full day, when we’d taken a cab out to Arashiyama, we returned to downtown Kyoto via the Randen line, departing from a station dubbed the kimono forest for its colorful poles. The train contained passengers with real kimonos, and that paired with the monkeys we’d just seen and the grass growing on the side of the tracks made me imagine we were heading off into the pastoral world of My Neighbor Totoro.

We capped off the trip with one final mad dash. At a nightclub at around 2am on our final night, I told Corey we had to leave to get some rest before heading to the airport the next morning. She said she’d be right behind me, but 15 minutes later was nothing of the sort, and I waded back into the crowd to drag her out from the front row. We got back to our room at around 3am.

Before passing out, I noticed a new Slack message claiming the bus would leave at 7:45am. I thought this must be a mistake — multiple prior communications had confirmed it to be 8:30 — so I sent a message asking for clarification.

By the time we woke up at 7:35, having slept through our alarms, no one had responded. I scrambled into the shower then threw on some clothes and — bags still unpacked and Corey still upstairs — arrived downstairs at 7:45 on the dot. A trek lead confirmed the bus would leave within 10 minutes, so I ran back upstairs, dumped all my clothes into the suitcase and jammed it shut, and we made it downstairs by 7:55, all packed, albeit barely.

We walked out of the hotel and down the street and found the bus still waiting for us. It left at 8:05 sharp, a full 25 minutes before its scheduled departure. Around half of the people who’d signed up for the bus had made it.

On the bus within 5 hours of stumbling home from the club

We cruised down Route 1, meeting virtually zero traffic, before shooting over a thin bridge out to the airport floating in Osaka Bay. As we pulled up to the gate and I spied a Vietnam Airlines plane on the tarmac, I thought how close we were to the rest of Asia. More adventure was just a short flight away; all I had to do was book.

We stuck with our flight back on Korean Air though, connecting first through Incheon International Airport. The first thing I noticed, as we approached mainland Asia, was the massive difference in air quality. As I write this blog in LA, known as one of our country’s most polluted cities, the air quality index is 54, or “Moderate.” As we landed in Seoul that day, it was 255, or “Very Unhealthy.” The smog obscured any decent view of the city.

Perhaps one reason why America is slow to take action on climate change is that its effects really aren’t that bad here. If you look at this list of the 100 most-polluted cities in the world, 65 are in India and 16 are in China. To find the United States, you have to scroll all the way down to Oakridge at #382. With California being the most-polluted state in the USA, it’s little wonder that it’s followed suit with China in a pledge to eliminate sales of gas-powered cars by 2035. It’s ironic how Americans consider our economy unparalleled in innovation — and justifiably so, given that our country, by far the richest in the world, generates 25% of global output with just 4% of the world’s population — yet we lag behind authoritarian regimes in such critical areas.

I took both of these photos on the same day:

Incheon, the 36th-most-polluted city in South Korea

California, the most-polluted state in the USA

Inside the airport, it was another world. After transferring gates, we walked into a gorgeous atrium, in which the air couldn’t have looked any cleaner. On our way to our gate, a robot pulled up, offering to take our bags for us. As I read my book at the gate, Corey slept, fully reclined, in the sumptuous public lounge.

Getting around in Japan felt overwhelming at first, so little did we understand the culture or the language. Yet after the initial shock, most of our struggles and annoyances in getting around came from our being part of a massive American tour group rather than any flaw endemic in the Japanese system. Indeed, moving around Japan was by-and-large far smoother and more seamless than any American city I’ve been to. NYC has a great subway but is so crowded and congested. LA feels more relaxed and spacious until you try to get to the other side of town during rush hour. In Tokyo, massive as it is, there always seemed to be an efficient means to get from one place to another, assuming we were wise or savvy enough to find it.

Thank you for reading! In the next post, we’ll delve into the culinary side of things, with plenty of sushi, soba, and sake.

All pictures and videos in this post were captured either by Corey or myself.